Article and photos from The Cultural Tutor (@culturaltutor) on Twitter...

If we couldn’t keep them cool, then glass skyscrapers and megacities in the desert would be impossible. This is how air conditioning changed the world — and influenced architecture everywhere we look.

In 1901 a New York publishing company needed to solve a major problem: the varying humidity in their factory made it very difficult to print in color. An engineer, Willis Carrier, solved it for them by inventing a machine which controlled both humidity and temperature.

Carrier realized the potential of his invention — though it was another inventor, Stuart Cramer, who created the term “air conditioning” — and founded a company to mass-produce these climate control machines. The world would never be the same again.

For almost all of human history one of our biggest challenges was to ensure that buildings were suited to their climate. Whether houses, castles, temples, granaries, or anything else, they had to deal variously with scorching heat, freezing cold, rain, snow, and wind.

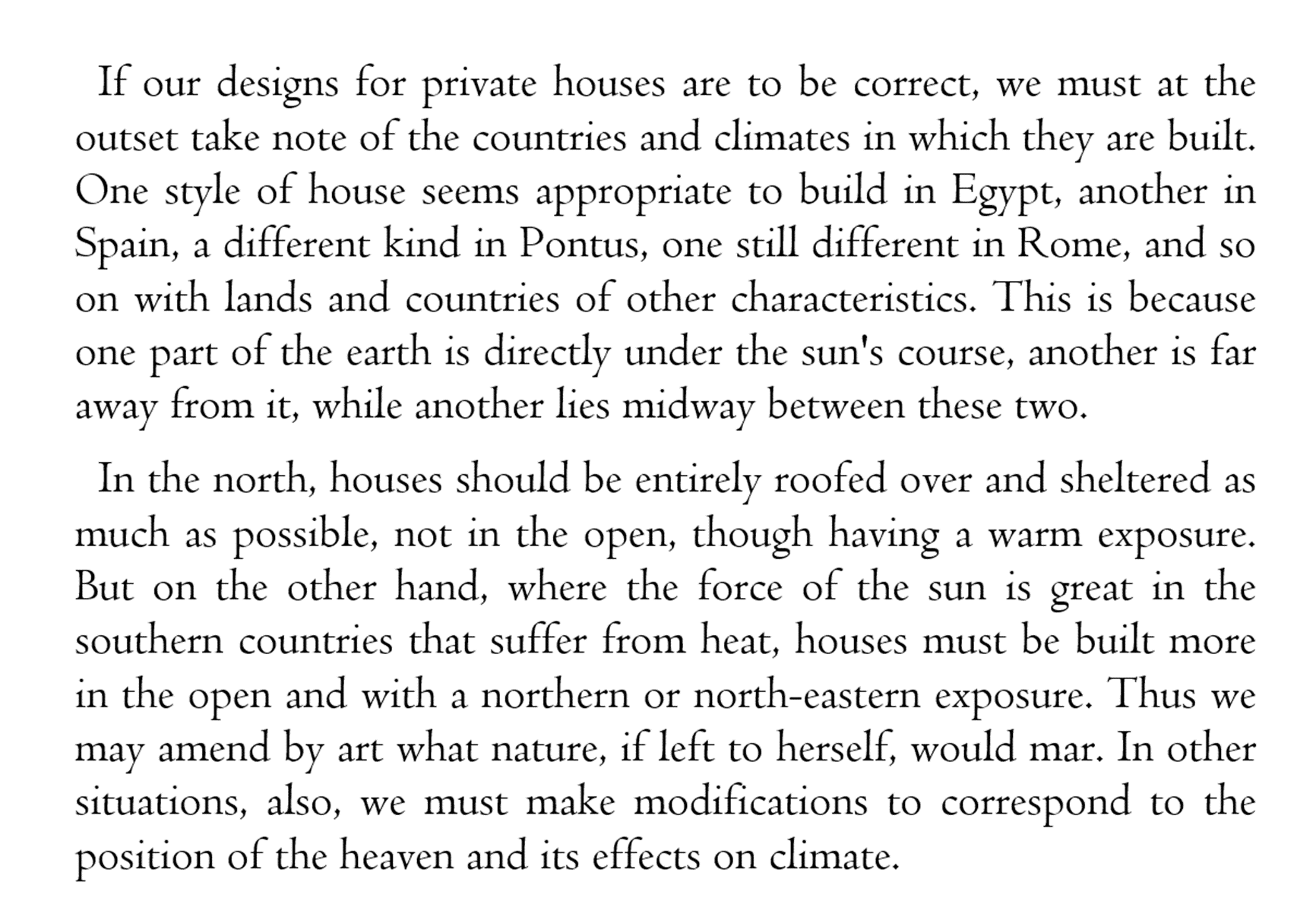

The Ancient Roman architect and military engineer Vitruvius wrote about this over 2,000 years ago. He explained that it would be impossible to build the same sorts of buildings in every part of the world, because architecture always had to account for local conditions.

Think of Scandinavian churches or German houses with their steep roofs — to prevent snow building up and causing a collapse. We may think they look charming now, but this was architecture and design responding to and developing in accordance with the local climate.

The traditional crofters’ cottages of Scotland were built with thick walls, small windows, and a big thatched roof to keep the rain out and the heat in. This was about staying warm and dry in a region that is wet and cold for most of the year.

Then you’ve got hotter regions, where the challenge is arguably even greater. For thousands of years people harvested ice from mountains or glaciers and used it to cool their houses, water, or food; in the 19th this became an international industry. How did architects and builders deal with the demands of hot and humid climates? Big windows, high ceilings, balconies, open spaces, and rooms below ground level. Think of a traditional Moroccan house with its large central courtyard, or the subterranean stepwells of India.

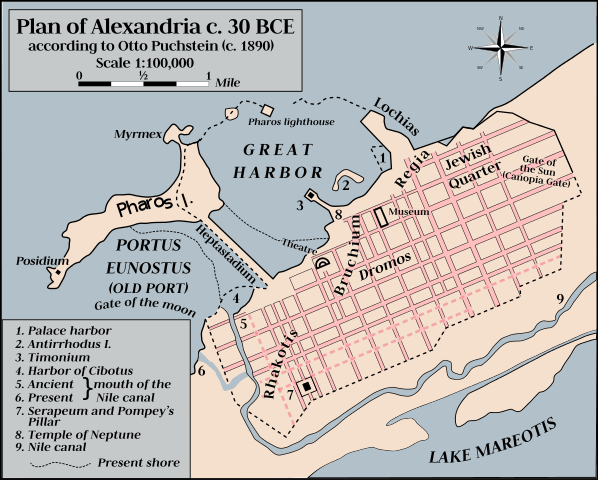

The porticos and colonnades of Ancient Greece and Rome provided shade during the day, while Indian jalis — intricately carved, perforated windows made from wood or stone — compressed the air which passed through them and, thanks to the Venturi effect, cooled it down. It was also important to design buildings and cities according to other environmental factors, not least water sources and prevailing winds. Dinocrates, the architect who planned Alexandria in 332 BC, ensured harsh northerly winds wouldn’t blow directly through the streets.

But this doesn’t even tell the full story. In the past people were also restricted by knowledge — it was a less globalised world — and, crucially, by whatever construction materials were locally available, be that pine, oak, limestone, marble, slate, reeds, clay, mud, turf…

And so, all over the world, from region to region and town to town, different styles of architecture emerged as a result of the need to address the local climate, as restricted by available materials and local cultural practices. This is where traditional architecture came from. Things started to change with the introduction of modern construction methods and materials, such as concrete, plate glass, girders, and steel. But the problems of dealing with local climate still necessitated differences in design and appearance. That is, until air conditioning.

In the 1920s a private air conditioning unit cost the modern equivalent of several hundred thousand dollars, but by the 1950s smaller, cheaper units had been invented. Increasingly, architecture and urban design didn’t need to account for the local climate. Suddenly traditional architecture — which first arose from necessity rather than choice — was no longer necessary. We could build the same sort of building everywhere in the world. And, aided by the forces of globalisation, that’s exactly what we’ve done.

Remember what Vitruvius said: once upon a time architecture had to be different everywhere in the world. Without air conditioning it would have been impossible to build the same form of huge concrete tower block in every region and city on earth. But air conditioning didn’t only change how buildings looked; it also revolutionized where they could be built and how big they could become. A city like Dubai could not exist without air conditioning — those colossal glass towers would be unbearable for living or working.

Between 1995 and 2005 the number of residential buildings in China with air conditioning rose from 8% to 70%. Other inventions, from modern plumbing to elevators, have also played a role in these changes. But the global homogeneity of architecture would not have been possible without air conditioning, because it solved the problem which for millennia had forced us to build differently.

The effects of air conditioning extend well beyond architecture and amount to something like a total revolution in the politics and economics of the world. To give but one example, how would server rooms function without it? The knock-on effects are endless.

So that’s air conditioning, which revolutionized the world of architecture and, among many other things, has completely changed how the world looks. And notwithstanding the rise of megacities and a single global style, it’s also responsible for these white boxes everywhere…